Madrassas the only choice for Afghan girls barred from school

Afghan BBC service, Kabul

BBC

BBCAmina will never forget the moment her childhood has changed. She was only 12 years old when she was told that she was no longer able to go to school like boys.

The new academic year started on Saturday in Afghanistan, but for the fourth year in a row, girls over the age of 12 were prevented from attending the classroom.

“All my dreams have been shattered,” she says, her voice is fragile and full of passion.

Amina, who is now 15 years old, always wanted to become a doctor. As a small girl, she suffered a defect in the heart and underwent surgery. The wounds that saved her life were a woman – a picture with her and inspired her to take her studies seriously.

But in 2021, when the Taliban restored power in Afghanistan, Amina’s dream was suddenly suspended.

“When my father told me that schools were closed, I was really sad. It was a very bad feeling,” she says quietly. “I wanted to get an education so I could become a doctor.”

The restrictions imposed on teaching teenage girls, imposed by the Taliban, have affected more than a million girls, according to UNICEF, the United Nations Children’s Agency.

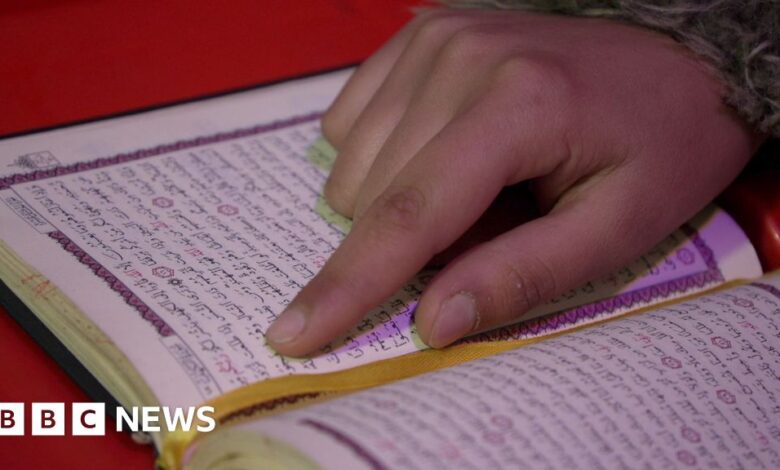

Now, schools – religious centers that focus on Islamic teachings – are the only way for many teenage women and girls to reach education. However, those whose families can withstand special tuition fees may still have access to topics including mathematics, science and languages.

While some people look at schools as a way to provide young women by reaching some education that they would have obtained in the prevailing schools, others say it is not a substitute and there are fears of brainwashing.

I met a secretary on the lower floor full of modern a teacher in Kabul, a newly created religious educational center for about 280 students of all ages.

The lower floor is cold, with cardboard walls and sharp cold in the air. After chatting for about 10 minutes, our fingers are already going.

The conversation was established as a year ago by Amina’s brother, Hamid, who felt that he had to act after he saw the ban on her.

“When girls were deprived of education, my sister’s dream was crushed to become a surgeon, which greatly affects her well -being,” says Hamid, who was in his early thirties.

He adds: “Getting an opportunity to return to school, as well as learning the tribe and first aid, made her feel a great improvement in her future.”

Afghanistan is still the only country where women and girls are banned from secondary and higher education.

The Taliban government originally suggested that the embargo be temporary, pending the fulfillment of certain conditions, such as “Islamic” curricula. However, there was no progress towards reopening schools for older girls in the years.

In January 2025, a report issued by the Human Rights Center in Afghanistan indicated that Madras is being used to enhance the ideological goals of the Taliban.

The report claims that the “extremist content” has been integrated into their approach.

She says that the Taliban’s textbooks promote their political and military activities, and have banned the mixing of men and women, as well as supporting the wearing of the forced veil.

The Afghan Center for Human Rights launches the ban on older girls who attend the school “a systematic and targeting” violation of their right to good education.

Before the Taliban returned, it is believed that the number of registered schools was about 5,000. They focus on religious education, which includes the studies of the Qur’an, the thugs, the arteries and the Arabic language.

But since the restrictions on teaching girls were presented, some have expanded the teaching of materials, including chemistry, physics, mathematics, and geography, and languages such as Dari, Pashto and English.

Although a few schools tried to provide training on the tribe and first aid, the Taliban banned medical training for women in December last year.

Hamid said he was devoted to providing education that mixed both religious academic subjects and other high school girls.

He told me with a smile, clearly proud of his sister’s flexibility: “Social communication with others has made my sister happier.”

We are visiting other schools that are ranked independently in Kabul.

Sheikh Abdul Qadr Gilani knows more than 1,800 girls and women from five to 45 years old. The student’s classes are organized instead of age. We managed to visit under strict supervision.

Like acute sharpness, it freezes the cold. The three -storey building does not contain heating, and some classrooms were missing doors and windows.

In one large room, two categories of the Qur’an and the sewing category are made at one time, where a group of girls who wear the veil and black face masks sit on the carpet.

The only heat in the school is the small electrical coolant in the director’s office on the second floor, Mohamed Ibrahim Barakzai.

Mr. Barakzai tells me that academic topics are taught along with religious people.

But when I ask for evidence of this, employees search for a while before some textbooks are presented to mathematics and science.

Meanwhile, the classrooms are well equipped with religious texts.

These schools are divided into two parts: official and unofficial.

The official section covers topics such as languages, history, science and Islamic studies. The informal section covers Quranic studies, modern, Islamic law, and practical skills such as sewing.

It is worth noting that the graduates from the informal section exceeds their number from the official section by 10 to one.

Hadi, 20, recently graduated from a teacher after studying a wide range of topics including mathematics, physics, chemistry and geography.

You talk enthusiastically about chemistry and physics. She says: “I love science. The whole matter is related to matter and how these concepts are related to the world around me.”

Hadiya is now teaching the Qur’an in a teacher, because she tells me that there was not enough demand for her favorite topics.

SAFIA, 20, also the Pashto language is a teacher. She enthusiastically believes that girls in religious centers should enhance what she described as personal development.

It focuses on FIQH, the necessary Islamic legal framework for daily Islamic practices.

“FIQH is not included in the prevailing schools or universities,” she says.

“Understanding concepts such as GHUSL – ablution – discrimination in the gender brightness, and pre -prayer requirements are decisive.”

However, she adds that schools “cannot be a substitute for major schools and universities.”

“Educational institutions, including schools and major universities are very necessary for our society. The closure of these institutions will lead to a gradual decrease in knowledge within Afghanistan,” they warned.

Toka, 13, a quiet, reserved student, who is also studying in Sheikh Abdul Qadr Gilani as a teacher. From a religious family, she attends lessons with her older sister.

“Religious themes are my favorite,” she says. “I would like to learn about the type of veil that a woman should wear, how her family should treat her, how to treat her brother and husband well and she is not rude to them.”

“I want to become a religious missionary and share my faith with people all over the world.”

The United Nations Special Rapporteur on Human Rights in Afghanistan, Richard Bennett, has sparked serious concerns about the Taliban “school” education system.

He stressed the need to restore educational opportunities for girls after the sixth grade and for women in higher education.

Mr. Bennett has warned that this limited education, along with high unemployment and poverty. ”It can enhance radical ideologies and increase the threat of local terrorism and threaten regional and global stability.”

The Taliban Ministry of Education claims that about three million students in Afghanistan are registered in these religious educational centers.

I promised to reopen girls ’schools under certain circumstances, but this has not yet been achieved.

Despite all the challenges faced by Amina – her health struggles and the ban on education – she is still optimistic.

“I still think that the Taliban one day will allow schools and universities to reopen them,” she says, with conviction. “I will realize my dream to become a heart surgeon.”

https://ichef.bbci.co.uk/news/1024/branded_news/8913/live/ea3eadb0-00cc-11f0-a8b1-950887ddc6e5.jpg

2025-03-24 23:11:00